Washing Away Debt: ZIPS Car Wash and the Cost of Private Equity Ambition

Despite the attention-grabbing headlines, the car wash industry remains robust and continues to attract investment due to several key drivers:

A recession-resistant business model that delivers consistent revenue through subscription memberships and loyal repeat customers; scalability with reasonable labor costs; strong consumer demand, bolstered by subscription models that ensure steady revenue for operators; and technological advancements, which improve operational efficiency, lower overhead costs, and boost profitability.

The situation at ZIPS Car Wash provides a vivid case study of how financial missteps, market dynamics, and competitive pressures can unravel a promising business in a high-growth industry. Below, I’ll expand on the key points, delving deeper into the mechanics of ZIPS’ challenges and their broader implications for the car wash sector and private equity investing.

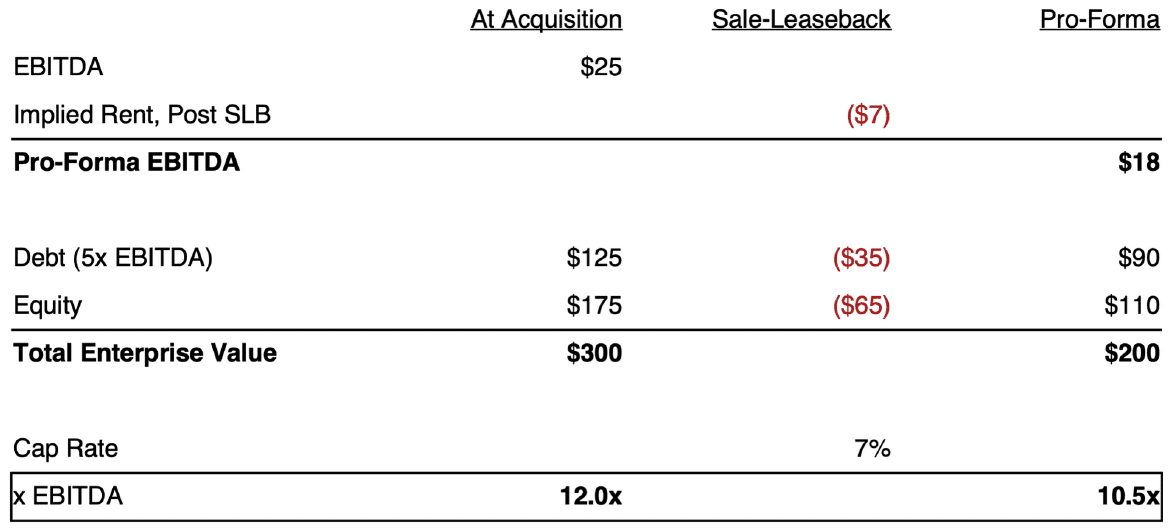

Let’s start by understanding sale-leaseback transactions and the mechanics behind them. A sale-leaseback occurs when a company sells an asset it owns—typically real estate, like a car wash facility in the case of ZIPS—to a buyer (often a real estate investor or REIT) and then immediately leases it back for a long-term period. This allows the company to continue using the asset while freeing up capital that was previously tied up in the property. Below is a simple example of how this can be executed.

By selling the real estate, the company pays rent under the lease, which is treated as an operating expense.

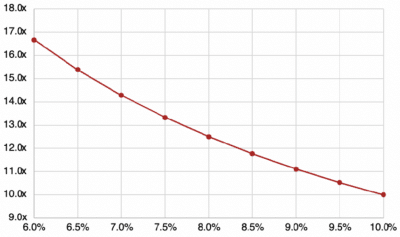

Cap Rate to Multiple Conversion

Theoretically, if you can perform a Sale-Leaseback on an acquired asset at a higher multiple (Cap Rate to Multiple Conversion Graph above) than you paid, it becomes an effective way to lower your entry cost by taking advantage of this arbitrage. As detailed in the example above, selling the real estate component of the business at a 6% Cap Rate, you are effectively selling a portion of your business for ~16.7x even though it cost you 12.0x – creating an arbitrage of ~4.7x.

This leads us back to ZIPS Car Wash, an early private equity-backed platform and the fifth-largest operator of express carwashes in the U.S. Atlantic Street Capital first invested in ZIPS in May 2020, purchasing a majority stake from thecompany’s founders. At that time, ZIPS had already established itself as a consolidator in the industry, having expanded to185 locations through 40 acquisitions during the 2010s. In the years that followed, Atlantic Street provided additionalequity to fuel further acquisitions, growing ZIPS’ footprint to 260 locations and increasing its revenue to $345 million. Large express car wash chains, with significant corporate overhead and rent payments due to divesting real estate via sale-leasebacks, typically operate with EBITDA margins of 35-45%, suggesting that ZIPS may have generated EBITDA in the range of $130-150 million at this stage.

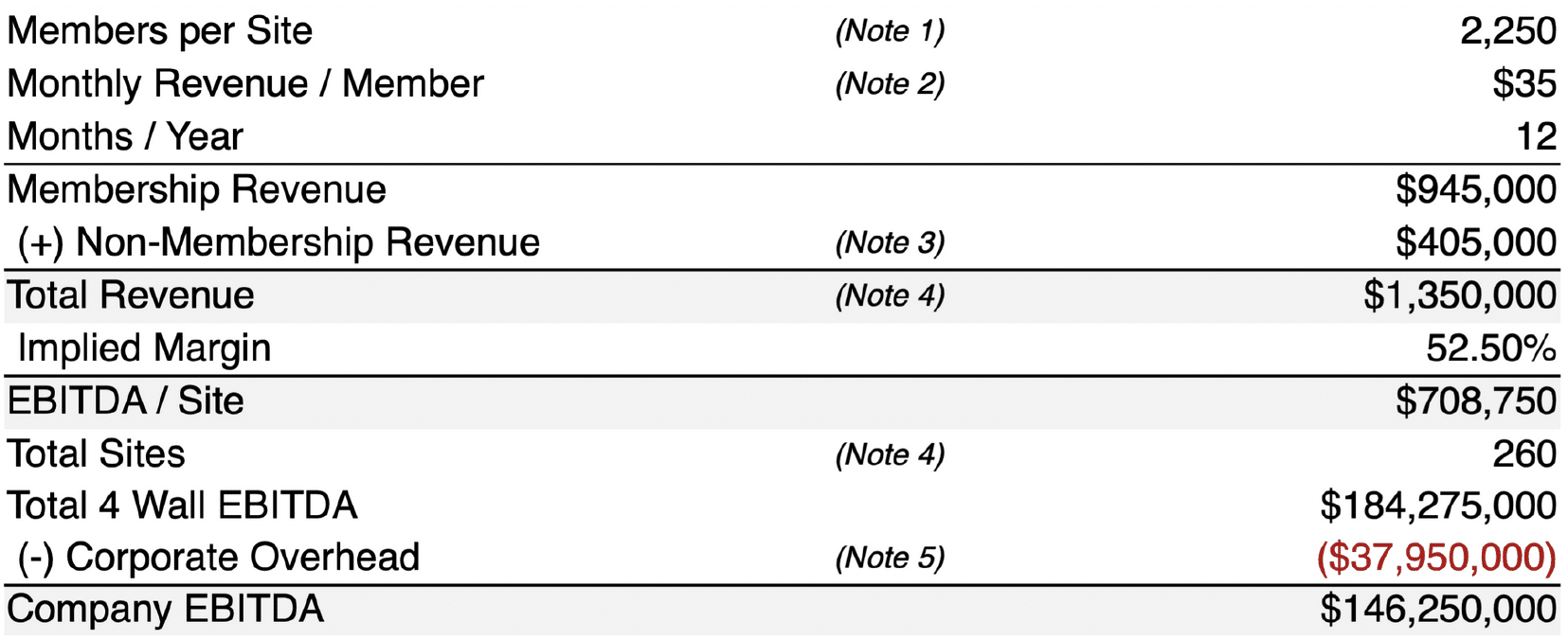

Below is an approximate breakdown of ZIPS’ unit economics, based on their filings.

ZIPS Estimated Revenue Build

Notes:

- June 2024 memberships per site based on CH. 11 filing

- Zip’s offers memberships ranging from $20 – $45. Estimation is based on proprietary data sourced by FOCUS

- Estimated based on CH. 11 filing’s that membership revenue is “over two-thirds” of total revenue

- Total revenue is approximately $350 million based on 260 units

- Estimated to be approximately 11% of revenue; same % as Mister Car Wash

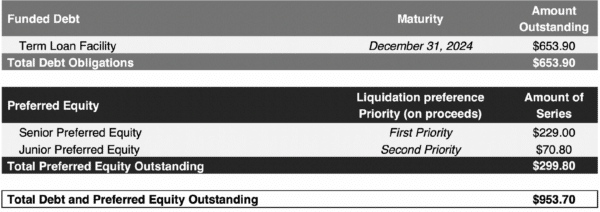

If the estimated $146 million of EBITDA at peak is true, raising $650 million of debt doesn’t seem off base. So – what happened to earnings?

If the estimated $146 million of EBITDA at peak is true, raising $650 million of debt doesn’t seem off base. So – what happened to earnings?

Notes:

- Amounts of Debt and Preferred Equity in millions

1. Mismanagement of Floating Rate Debt and Escalating Interest Costs

ZIPS’ failure to effectively hedge its floating rate debt exposed it to significant financial strain as interest rates climbed. In 2023, interest expenses on its term loan ballooned to $93 million, a sharp increase from $59 million in 2022. With a debt load exceeding $650 million, this translates to an average interest rate of roughly 14% in 2023—exceptionally high for a business reliant on consistent cash flows. This surge in interest costs devoured a substantial portion of ZIPS’ operating cash flow, diverting funds that could have been reinvested into growth initiatives, operational improvements, or debt reduction.

The absence of robust hedging strategies left ZIPS vulnerable to macroeconomic shifts, particularly the Federal Reserve’s aggressive rate hikes to combat inflation. Floating rate debt can be a useful tool when interest rates are low and predictable, but without adequate protection—such as interest rate swaps or caps—ZIPS was at the mercy of rising rates. This misstep not only strained its balance sheet but also eroded investor confidence, as lenders likely grew wary of the company’s ability to service its debt. The result is a likely scenario where term loan lenders, holding senior claims, will take control of ZIPS’ equity, wiping out both preferred and common equity holders. This outcome underscores a critical lesson: in leveraged businesses, proactive debt management is non-negotiable.

2. Inflationary Pressures and Pricing Constraints

Inflation further compounded ZIPS’ woes, driving up operating costs at a time when raising prices was fraught with challenges. Labor, the largest cost driver aside from rent, has seen significant wage inflation in recent years, particularly in service-oriented industries like car washes. This can also be attributed further to the increase in competition, as car wash industry experts now have multiple employers they can work for, allowing for strong talent to demand higher compensation. Another strongly cited point is chemicals, which should not be looked at in a vacuum. While chemicals used in the washing process are relatively inexpensive— approximately less than $1 per wash—their costs have also ticked upward due to supply chain disruptions and raw material price increases. These rising expenses squeezed margins, as ZIPS and other operators had limited levers to offset them without alienating customers. While these costs and increases may seem insignificant, the impact magnifies exponentially when the top line revenue of several locations begin to diminish in addition to these rising costs. If a location sees fewer customers, its fixed costs (like labor, chemicals or rent payments from a sale-leaseback) remain unchanged, but revenue drops. This underutilization makes it harder to cover costs, further squeezing margins.

Raising prices might seem like an obvious solution, but this is not as easy in a saturated market. In markets like the Southeast, where ZIPS is concentrated, car washes are often a “nice-to-have” rather than a necessity, unlike in regions where road salt necessitates frequent cleaning. Customers in these southern markets are much more price-sensitive and can easily skip a wash or opt for a competitor offering lower prices due to the saturation. The influx of new car wash locations, fueled by the industry’s attractive return on invested capital (ROIC), intensified this pressure. New entrants, eager to capture market share, often kept prices competitive, making it difficult for established operators like ZIPS—particularly those with older sites—to pass on cost increases without risking customer defections. This dynamic trapped ZIPS in a cycle of rising costs and stagnant to declining revenues, further eroding profitability.

3. Oversupply

The oversupply of car washes reflects a broader issue in high-growth industries: uncoordinated development. Operators, lured by low-cost debt, sale-leaseback financing, and the promise of recurring revenue, rushed to open new sites without fully accounting for site quality and market saturation. ZIPS itself contributed to this trend, but as its Chief Development Officer presciently warned in a Bloomberg article a year ago, overbuilding risks a “survival of the fittest” scenario in certain trade areas. When supply outpaces demand, even a growing market can become unprofitable, as operators undercut each other to maintain volume. For ZIPS, this translated into declining same-store sales and likely significantly lower EBITDA, as revenue growth stalled while costs continued to climb. This created a crowded marketplace where operators competed for a finite pool of customers.

Oversaturation often leads to cannibalization, where new car washes—sometimes even from the same operator—steal customers from existing locations. In ZIPS’ case, its rapid expansion to 260 locations (from 185) through acquisitions likely contributed to this problem. If new ZIPS locations were opened too close to existing ones, they may have drawn customers away from older sites rather than capturing new demand. Each new car wash siphoned customers from existing sites leading to attrition.

Broader Implications for the Car Wash Industry and Private Equity

The car wash industry’s challenges highlight two critical themes in investing: navigating industries with rapidly growing supply and demand and avoiding the “lemming effect” of overcrowding a trendy sector.

Rapid Supply and Demand Growth:

The car wash sector initially seemed like a goldmine. With nearly 300 million cars in the U.S., rising consumer interest in outsourcing low-cost services, and new locations stimulating demand (e.g., a conveniently located car wash prompting more frequent visits), the industry offered compelling economics. High ROIC, reduced operational burden due to technology, and recurring revenue from subscription models made it a magnet for operators and investors. However, the uncoordinated rush to build new sites disrupted this balance. When supply grows faster than demand, even a promising market can falter, as ZIPS’ experience illustrates. Investors must carefully assess whether growth projections account for competitive dynamics and potential oversaturation.

The Lemming Effect:

The car wash boom exemplifies what happens when too many players pile into a “hot” industry without a clear exit strategy. Private equity firms, drawn by low-cost debt and the prospect of high returns, backed numerous car wash platforms, many of which were founded in recent years to capitalize on the land grab. However, as the industry matures the pace of development inevitably slows and valuations shift from being driven by future growth potential to the cash flows of existing units. This transition risks EBITDA multiple compression, as buyers prioritize profitability over speculative upside. Moreover, with only a handful of large-cap PE firms capable of acquiring mid-market platforms, weaker performers like ZIPS face the prospect of being stranded without a buyer. The lemming effect—where herd behavior leads to overcrowding and diminishing returns—underscores the importance of disciplined market entry and a clear path to exit.

ZIPS’ Outlook and Lessons Learned

ZIPS’ financial and operational struggles suggest a grim outlook. With EBITDA likely cut by more than half and interest costs consuming cash flow, the company’s equity is poised to be handed over to its term loan lenders. This outcome reflects not only ZIPS’ missteps but also the broader challenges of operating in an oversupplied, highly competitive market. The company’s inability to hedge its debt, raise prices, or differentiate itself from competitors left the company ill-equipped to weather the industry’s growing pains.

For investors and operators, ZIPS’ story offers several takeaways:

Debt Discipline: Hedging strategies are critical for businesses with significant floating rate debt, especially in volatile rate environments. Maintaining discipline with business debt requires a strategic and proactive approach to ensure financial stability and growth. Start by creating a clear budget that prioritizes essential expenses and allocates a consistent portion of revenue toward debt repayment, avoiding the temptation to overspend on non-critical areas. Regularly review your cash flow to identify opportunities to pay down debt faster, such as cutting unnecessary costs or redirecting profits during high-performing months. Avoid taking on new debt unless necessary, and when you do, carefully assess the terms—opt for lower interest rates and realistic repayment schedules. Finally, treat debt as a tool, not a crutch, by using it to fuel growth (like equipment purchases or expansion) rather than to cover operational shortfalls, ensuring you’re always in control of your financial obligations.

Consider Market Saturation & Oversaturation: High-growth industries require careful analysis of supply dynamics to avoid overbuilding and margin erosion. As noted earlier, the “lemming effect” drove many operators to pile into the market, but this led to diminishing returns as supply outpaced demand. Further, one can succumb to this phenonium on their own, even if unintentionally, by over densification within a specific market, leading to cannibalization.

Exit Planning: Private equity investors must prioritize platforms with sustainable competitive advantages and clear paths to exit, rather than chasing crowded trends. For owners, exit planning for a business involves a deliberate strategy to transition ownership or operations effectively, ensuring maximum value and a smooth departure for the owner. Begin by defining your goals—whether it’s selling to a third party, passing the business to family, or liquidating assets—and set a realistic timeline, ideally years in advance, to prepare. Assess the business’s value through a professional valuation, then enhance profitability and streamline operations to make it attractive to buyers or successors, addressing weaknesses like over-reliance on the owner or inconsistent revenue. Develop a succession plan or sale strategy, including legal and financial preparations like updating contracts, minimizing tax liabilities, and consulting advisors such as accountants or investment bankers.

Buy Based on Value, Not Potential: Buying a business based on value rather than potential is a smarter approach because it grounds your decision in tangible, proven results rather than speculative promises. A business’s current value—reflected in its revenue, profit margins, customer base, and operational stability—offers a concrete foundation you can assess and build upon, minimizing risk. Potential, while enticing, often hinges on untested assumptions like market shifts, your ability to fix inefficiencies, or future growth that may never materialize, leaving you overpaying for a dream. Focusing on value ensures you’re investing in a track record of performance and provides a clearer picture of cash flow and return on investment from day one. By prioritizing what’s real over what’s possible, you protect your capital and position yourself for sustainable success.

Download Full Case Study Here.