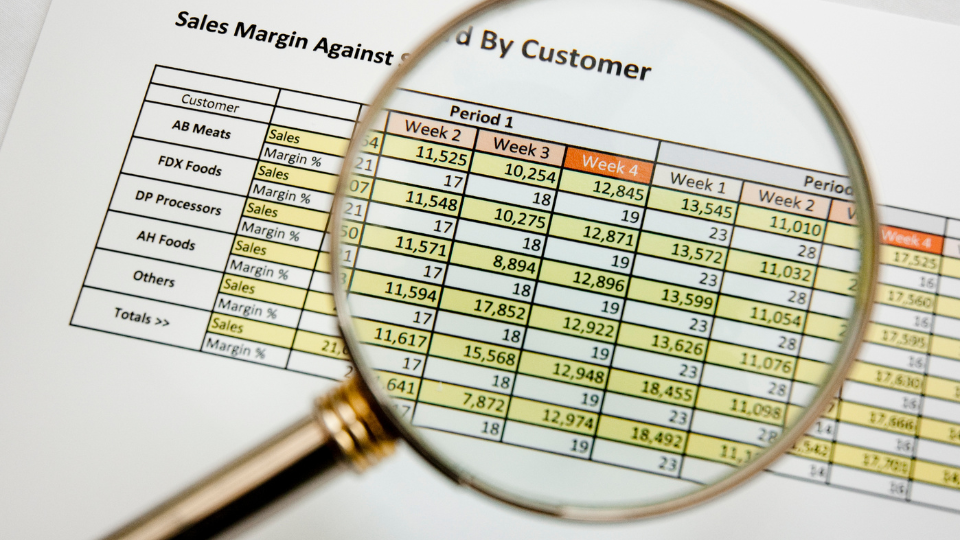

If you’re considering the sale of your consulting or professional services business, you should understand that buyers will be examining your Gross Margin as an indicator of the value of your firm. In situations where two companies have similar EBITDA, the one with the higher Gross Margin will normally get a higher transaction price, other things being equal. Why is this?

When calculated accurately, Gross Margin is a good indicator of the overall value of the services the company provides to its customers. Higher Gross Margin companies typically provide complicated, high-level consulting for which they can bill at a premium rate per hour. These high-value services can often generate true Gross Margins of 35% to 45%. By comparison, if the services offered are more widely available, then margins might be closer to 20% to 30%, as competitive pressures put a lid on the rates that can be charged.

Professional services companies make money by billing out their experts and consultants at rates higher than the employee cost. The bigger that gap, the bigger the Gross Margin. So, business owners often try to show the highest margin possible.

But there are rules about how to calculate that. It’s important to understand them so you don’t mislead yourself—or any potential buyers who may be interested in buying your company.

First, a common accounting error businesses make is only classifying an employee’s billable hours under Cost of Services or Cost of Goods Sold in the income statement. If your client service employee Mary, for example, works 1,000 hours in a year, but has the capacity to work 2,000, then her utilization rate was 50%. Some owners will only include half of Mary’s salary in Cost of Goods Sold, (as those were the only hours where Mary generated revenue) and put the rest of her salary in Sales, General and Administrative (SG&A) costs, below Gross Profit/Gross Margin.

While the final net income number may still be correct, your Gross Margin is overstated, because Mary’s full salary should be included in the Cost of Goods Sold.

Second, other costs directly associated with employees in a client-service role must be included in Cost of Goods Sold. That includes payroll taxes associated with those employees as well as their benefits costs. therefore, those items in SG&A expenses is incorrect and overstates your Gross Profit and therefore your Gross Margin.

Finally, if the owners of the business are also in a client service role and are not paying themselves a market rate for their salary, Gross Profit (and EBITDA) will be overstated, especially for how the business will be accounted for as part of an acquisition.

Bottom line: Be prepared for a thorough discussion of Gross Margin, in addition to EBITDA, when you are talking with your sell-side financial advisor or a potential buyer about the sale of your business.

Kelly Kittrell has more than 30 years of merger & acquisition and corporate finance experience. He advises business owners on sell-side and buy-side transactions, valuation analysis, corporate finance and equity and debt financing. Contact Kelly at [email protected].