NextGen has been called the most complex systems integration challenge ever undertaken by the federal government. In the beginning, NASA’s role in guiding the progress of the innovation that would become NextGen was significant, and I have been involved from the beginning.

In 2000, NASA sent me to work in the White House Office of Sciences and Technology Policy, supporting the foundations of what became the NextGen Concept. I was then asked by NASA and the FAA to join about a dozen others to form the Joint Planning Office, encouraging us to start from a clean slate, rethinking the possibilities. We had to develop the strategies for transformation and had a mandate from NASA to pull out all the stops.

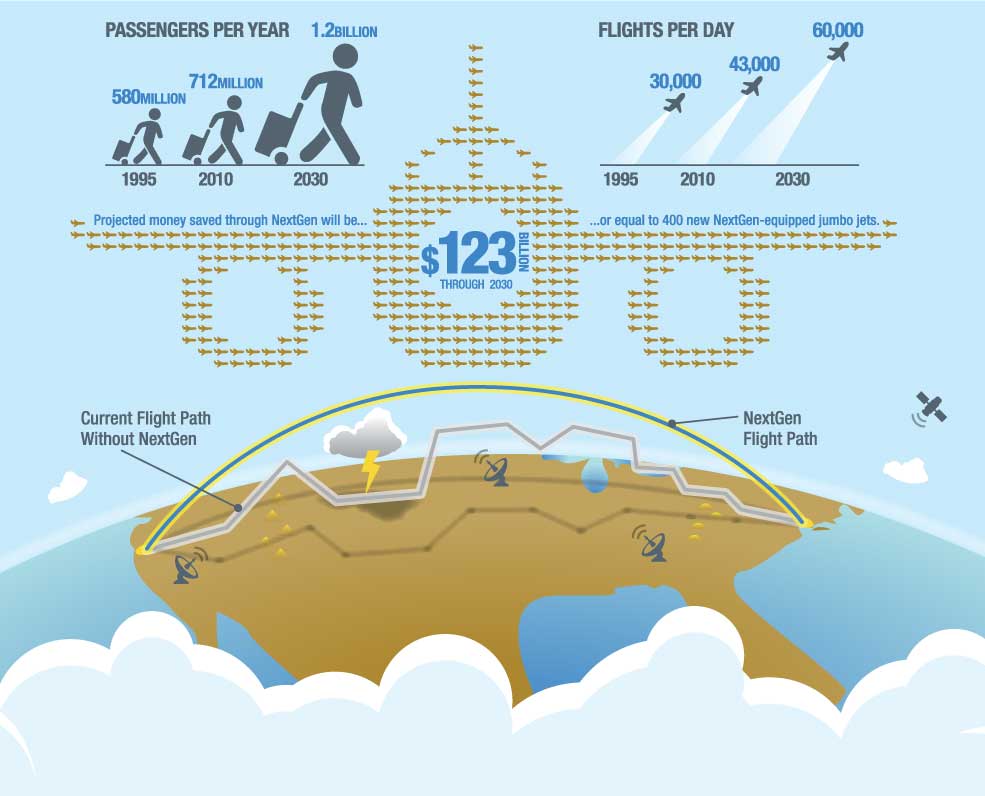

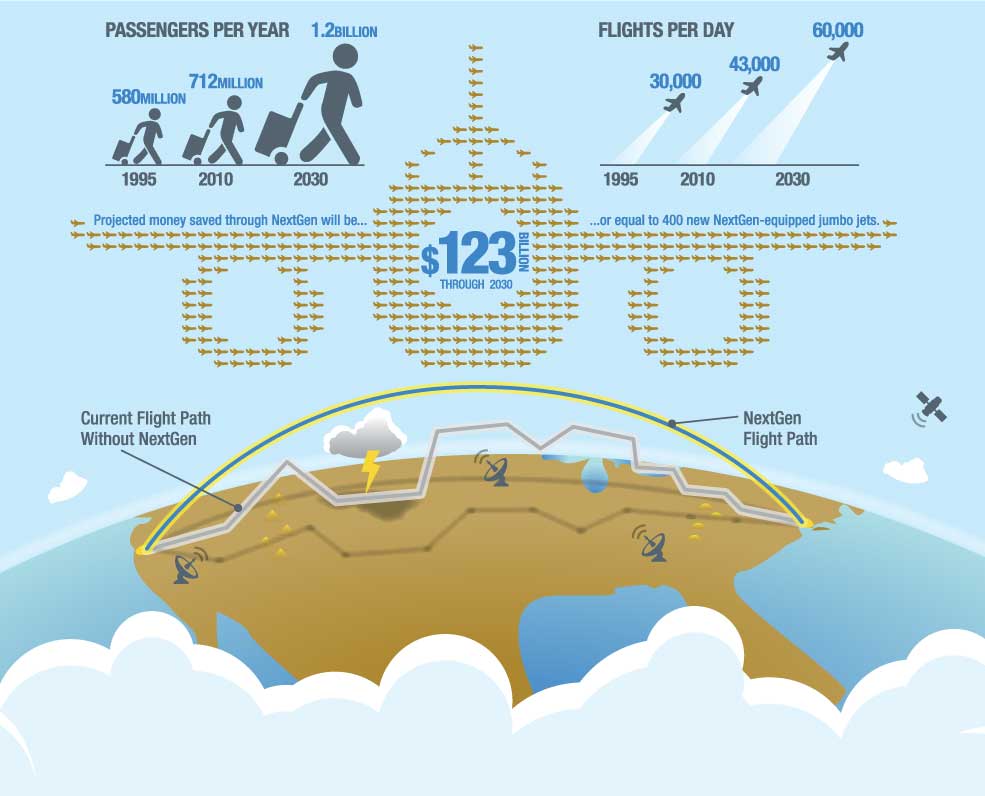

Image source: FAA

Gradually, the initiative transitioned from the planning and visionary phase to mapping a strategy for practical implementation. The FAA began to assign people to the project, moved the operation under FAA headquarters, and officially formed the Joint Planning and Development Office ( JPDO). By 2004, NASA turned its primary focus to long-term fundamental research, and the FAA picked up leadership for implementation of the initiative.

Fast forward to 2012—today, the FAA continues to take the leadership for the implementation of the NextGen vision, while NASA focuses on longer-range technology strategies. NASA also is charged with responsibility for what I like to call “the rest of the NextGen story,” which includes such things as aircraft, airport, and airspace capability beyond the time frame of the FAA’s role. In March 2012, the FAA published a NextGen Implementation Plan, which goes to 2018. Called a “midterm” plan, it describes a significant amount of progress being made and the challenges remaining.

International Progress

In Europe, the counterpart of JPDO is SESAR (Single European Sky ATM Research) Joint Undertaking—a collaborative project to overhaul European airspace and its air traffic management. As a co-founding member of the Joint Undertaking together with the European Commission, EUROCONTROL plays a key role in all SESAR efforts. Some of the institutional and systemic advances needed in NextGen are happening earlier in Europe than in the U.S., because of their top-down directed institutional administration.

For example, Europeans already have flown the first fourdimensional trajectory-based operations. In a recent interview, SESAR’s Executive Director Patrick Ky noted, “We in Europe need to implement the four dimensional separation capability by 2018—we are not going to wait for the U.S. until 2030.” According to Mr. Ky, the reason is simple: “We cannot afford the cost of money over the added years.”

Investors will want to understand that even though the Europeans may accelerate their systemic implementations of new technologies and policies, in the end, the much more innovative business and regulatory climate in the U.S. helps us move some things much faster. For example, advancements in business and general aviation have outpaced innovation anywhere else in the world. The fact that air transportation advancements are taking place under the umbrella of international cooperation and standard-setting creates a positive situation for investment opportunity. International Harmonization From a U.S. preferred vision of the world, we would be writing the standards for aviation manufacturing and operations, and everyone in the world would buy our systems. This vision was, in actuality, a fact for many decades, but it is not a reality anymore. While some will bemoan our loss of technological leadership, the reality is that U.S. companies are no longer the sole purveyors of products and services overseas. In the past four or five decades, we have seen our aviation and aerospace market share go from nearly 99 percent to about 50 percent.

Harmonization between NextGen and SESAR is an advantage to both sides. Even though the two initiatives sometimes seem competitive, in the end competition is going to come from the private sector—not from either government. In fact, harmonization’s establishment of standards for products that can be sold internationally is positive because investors here can rely on a framework of technology, regulation, and finance based on solid international standards. Another plus is that even though the U.S. market share has declined over recent decades, the total world-wide market has grown, making the U.S share grow as well in absolute value.

Who is Going to Pay for NextGen?

When we began planning NextGen in the early 2000s, we knew that the transformation would move us from a ground-based, analog, human-centric system for managing air transportation to a space-based, digital, and more automated system for the 21st century. The major challenges ahead include establishing the role of humans interacting with automation, determining the redundancy and reliability requirements for such concepts as automated control towers, and changing the decades-old standards for spacing of aircraft, for example.

Many of the functions we have practiced from the ground, in the past, will be moved into the cockpit in the future. The question is—who pays? We paid for the current infrastructure from a combination of airline ticket taxes, passenger charges, etc. In the future—as currently planned—the FAA is asking the airlines to buy the equipment to do the job. In response, the general aviation community is saying, “Hey, wait a minute. You’re asking me to own this equipment? As my costs increase, your costs decrease. Is that fair?”

Opportunities in Transformation

The business case being made by the FAA is that equipping airplanes for NextGen will create a more efficient National Airspace System with improved reliability and environmental benefits in terms of noise and emissions. Currently, we cannot predict accurately how much it will cost airplanes to be NextGen equipped because innovations are happening so fast in the marketplace.

The many predictions by analysts about the cost of equipping aircraft and airports for NextGen often miss this key fact regarding the relentless effects of innovation in our industry. At the EAA Air Venture 2012 in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, avionics suppliers announced new equipment for NextGen, some that can be installed in general aviation aircraft for $5,000 to $10,000. Therefore, we see that transformation is taking place, and we can expect NextGen innovators to continue to make advancements in the performance and cost of the equipment we need to fulfill the NextGen vision. Mid-Atlantic Reg

About Dr. Bruce J. Holmes:

In addition to being a FOCUS Senior Advisor, Dr. Holmes is a co-founder of NextGen AeroSciences, and principal in Holmes Consulting. Currently, he sits on the FAA Research Engineering and Development Advisory Committee (REDAC) and serves on NASA’s Aeronautics Research Roundtable hosted by the National Research Council.

Dr. Holmes retired from 33 years with NASA as their Chief Strategist at Langley Research Center. As a member of the federal Senior Executive Service he served in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy on national air transportation system strategies, and led in development of the U.S. Joint Planning and Development Office (JPDO). He also led the creation of the NASA AGATE (Advanced General Aviation Transport Experiments) Alliance and the SATS (Small Aircraft Transportation System) program.

Dr. Holmes has been involved in a full spectrum of aeronautics research, from fluid physics to network science implications for transportation systems. His championing of the Highway in the Sky concept was the focus of a CBS 60 Minutes program; he has also appeared on Discovery and History Channels, and in NASA programming. He has published over eighty technical papers, received four patents, and been honored with numerous NASA medals and professional society awards, including as a member of the team receiving the prestigious Collier Trophy.